"Blaue Stunden. Kleine Quadratur der Liebe"

Erzählungen, Offizin-Verlag, Zürich 2015

Buchumschlag:

|

|

Textauszug aus der Erzählung Fading :

[…] Wochenlang hatte der tote Hund auf den Steinen gelegen. Sein verkohltes Fell hatte schon nach wenigen Tagen begonnen, auf die Umgebung abzufärben, hatte den feinen Sand, die Disteln und Grasbüschel, die in den Spalten der Steine wuchsen, in eine schmutzig graue Wüste verwandelt. Zuletzt war sein aufgedunsener Leib geplatzt, man sah Teile des Skeletts und ein paar lederartige Schläuche, die dunkel unter der Haut glänzten. Es roch nach nichts, nur der Duft nasser Kiesel umfloss die Stelle, an die wir, wie unter Zwang, immer wieder zurückkehrten. Vor dem Einschlafen versuchten wir, den Anblick zu vergessen, doch schon am nächsten Morgen, noch auf dem Schulweg, sahen wir wieder nach dem Tier, machten den kleinen Umweg am Ufer entlang, standen scheu und wie gebannt vor dem Schauspiel der Verwesung. Auch am Nachmittag zog es uns wieder an den Ort, nie begannen wir ein Spiel, ohne zuvor dem Hund einen Besuch abgestattet zu haben. – Erinnerst du dich? Zu niemandem ein Wort, hatten wir uns geschworen, weder zuhause, noch in der Schule. Das heilige Wesen gehörte uns, uns ganz allein.

Doch eines Tages war der Kadaver verschwunden – Nein, natürlich, du erinnerst dich nicht, denn du warst ja damals gar nicht dabei. Es war vor deiner Zeit. Irgendwo gab es dich schon, doch jenseits des Ufers, in einer Welt mit anderen Flüssen, anderen Kindern und anderen Toten. Doch an jenem Tag, Ende Juli, von dem ich erzählen möchte, da kamst du dann wirklich auf mich zu, ich sehe noch ganz deutlich, wie du beim Gehen größer und größer wurdest. Du hattest am Ufer auf mich gewartet, mit der Kamera in der Hand. Als ich dann zu lange stehen blieb, weil ich meinte, die Stelle gefunden zu haben, an der der Hund gelegen hatte, gingst du mir ein paar Schritte entgegen. „Komm“, sagtest du mit einem Lächeln, „komm zu mir. Ich bin der Wassergeist“. Ich lachte, nahm deine Hand und war froh, dass du dich nicht als „Vater Rhein“ vorgestellt hattest.

Dann hast du mich ins Licht gerückt, mir befohlen, die Schuhe auszuziehen und mit nackten Füßen durchs Wasser zu gehen. Ich durfte nicht in die Kamera blicken, du wolltest mich „erwischen“, von der Seite, von hinten, aus der Ferne. Als würdest du mir in den Rücken fallen, oder als hätte ich vergessen, dass du da warst. Wahrscheinlich aber wolltest du nur sehen, wie ich entschwinde, wie ich mich im Wasser verliere, ganz allmählich – kleiner und kleiner werde, um schließlich den Moment einzufangen und sichtbar zu machen, in dem ich in die Vergangenheit tauche, wieder zum Kind werde. Das hättest du festgehalten und gerettet.

Doch ich konnte die Stelle, an der der Hund gelegen hatte, nicht finden. Die Wege hatten sich geändert, das Gebüsch und der kleine Wald waren verschwunden. Ich hatte ja schon Mühe gehabt, den Weg zu unserem alten Haus zu finden. Es war heruntergekommen, halb verdeckt von hohen Bäumen und zur Straßenseite hin eingekesselt von neuen Häuserblocks. Du gingst neben mir her, und ich redete auf dich ein, erzählte dir, wie alles gewesen war, wie damals die Straße verlief, wo meine Schule gestanden, wie unsere Küche bei Hochwasser gerochen hatte. Wenn wir stehen blieben, legtest du den Arm um mich, ließest dir alles zeigen und erklären, geduldig, ganz als wären diese Dinge wirklich wichtig. Ich weiß nicht, wie es kam, dass mir an diesem Tag alles so neu und so fremd erschien, warum ich meine Kinderwelt mit anderen Augen sah. Wahrscheinlich waren es deine Augen, deine wachen, dunklen Augen, deren Suchen mir fast weh tut, wenn es an mir hängen bleibt und mich zu sich hinein zieht. Diese Augen sahen alles neu. Und so fielen die alten Bilder, nach und nach, von mir ab wie zerlumpte Kleider. An ihre Stelle traten die anderen – deine Bilder: bunter, deutlicher als die alten. Dein Blick hat alles neu belichtet, die alte Schicht überblendet, ja nahezu ausgelöscht.

Am Abend zuvor hattest du mir erklärt, wie man das Luminanzrauschen technisch in den Griff bekommt, was man während der Aufnahme und später dann am Computer tun konnte, um zu verhindern, dass digitale Bilder von Störungen überlagert werden. Ich hörte dir zu, lag dabei halb auf deiner Brust, folgte mehr dem Klang als dem Sinn deiner Worte, spürte, wie sich jeder Ton aus deinem Atem aufbaute, tief in deinem Brustkorb zündete, um dann irgendwo draußen im Zimmer zu verhallen. Ich schloss die Augen und sah uns am anderen Ufer. […]

Übersetzung der Erzählung An jeder Ecke lauert das Glück. Strichcodes

Happiness is just around the corner. Bar codes.

It was some airport – probably Frankfurt – and I was in a hurry. My connecting flight to Amsterdam (or was it Copenhagen?) had been called long ago, and the information “Now boarding” flashed incessantly on the board overhead. I raced down the escalator, almost tripping over a suitcase that was blocking the way. “Excuse me, can I get past?” I asked the man with the suitcase, perhaps a little louder than necessary, “My flight leaves in five minutes!” The man turned around and his eyes flicked over me for a second, amused. “Go on then, run!” he said familiarly, as if to a child, and shifted his case across. So I ran, as quickly as is possible encumbered by boots and coat and rucksack. And yet something held me back, made me put the brakes on inside. I went through the motions, mechanically putting one foot in front of the other as if I still meant to catch the flight, but my inner schedule had suddenly changed. Our exchange had lasted three seconds at most, three seconds in which I had sensed his body close to mine, heard his voice and – how should I put it? – felt the spark.

Love and hunger begin with a transgression. The old gods and the animals know that, hunters and hunted alike. For me, it was a lesson I had to learn. I thought about that man on the escalator for months, the brazen guy who had stood there with his suitcase in the way and spoken to me so familiarly. I no longer remember what he looked like – he had glasses, I know that, fair hair, tall, mid-range voice, southern accent. But those are just the individual pieces of the jigsaw, splinters of an undefinable whole, a whole that was gone in seconds, that flew past me, up and away, and was lost forever.

Oh yes, and then there was that other guy recently on the train, or the one at the petrol station, and that nice busker on the Piazza in Florence, and of course the man I saw on the way to Davos, how could I forget him? I almost slipped my phone number to a couple of them, but on the train there were other passengers around, and the busker was surrounded by a crowd when he looked at me. How could I have managed, discreetly, to find out if he really was who I thought he was?

In love, I have realised over the years, there are two competing theories: the “one-person model” and the “many-people model”. With the “many-people model”, you only really need one – I mean anyone – but with the “one-person model” you need many. Because with the many-people model it doesn’t matter so much. Whether you choose this one or that one – at the end of the day you could live with all of them more or less happily, somehow, or at least with many of them, because they are all much of a muchness, so to speak. One simply loves everything and everyone – potentially at least. So you can settle for first-best or second or third and save yourself the bother of continuing to search, because statistically the first one is just as likely to be your perfect partner as the 3,344th. There’s no need to keep count even, because you could be happy enough with the first one.

The “one-person model” works in completely the opposite way: it revolves around the idea of archetypes and fate. The one-person model is absolutist, idealistic, terroristic in its concept of happiness based on ardour. We are like Plato’s ball people who in a kind of big bang of separation have been torn apart and scattered and ever since then have been living in a state of eternal schizophrenia, wandering through the cosmos in search of love, always looking for our lost half. “Where are you my lover?” “Where are you, my loved one?” Lost in the misty mountain forests of Kilimanjaro? Hidden in a hydrothermal crevice at the bottom of the ocean? Missing in the mangrove swamps of the gulf of Guayaquil? Hello? Hellooo?

“Oh oh oh oh oh,” comes the echo bouncing back. But in that vast hall of echoes it is impossible to locate where the sounds are coming from or to decipher their meaning.

The only thing to do is to keep searching, seeking, again and again, always starting over – tirelessly, unstintingly, forever. Because there is only one person who can be the one and only, “the one”, the forever missed and longed for other half. That much is clear – it’s what the whole model is based on. Maybe he/she/it is just around the corner, and if not there, then maybe a few streets further away. If only you knew at least what they looked like! Then at least you’d have a kind of e-fit image on which to base your search. But you don’t even know their hair colour – on a particularly lonely day even green would do, or purple, or maybe even a wig or a toupée. So how on earth are you supposed to recognise the one, the only, the dream man or dream woman, the Ur-person, among the madding, heaving crowd? What name do you call? On Kilimanjaro it would be easy, or on the beaches of Ecuador. And if you met him or her at 6,000 metres under water, surely the current would propel you into each other’s arms. But here in Frankfurt, in Paris, in Shanghai or in Cape Town, among the multitudes, the three million, fifteen million or twelve and a half million inhabitants, among all those people? In the hectic inertia of the crowd, in the futile rushing of the passers-by?

In the olden days in the village, when Hans and Greta or Max and Mina met by chance at a neighbour’s, one looked right, the other looked left, they shot a furtive glance behind them, or one felt the gaze of the other on their neck, and then they went home and life carried on. But they knew they would see each other again, maybe at the winter festival or just out on the street. Perhaps it would be as easy as asking your aunt who the good-looking boy with the dark moustache and the grey jacket was and she would tell you his address and full family tree, along with a bunch of gossip – to whom his sister was married, when his mother had died and with whom his father had quarrelled. Then you would know all the important stuff, and you could wait and dream until one day, probably quite soon, you would see him again and get engaged on the spot. That was how it used to be – in the country at least.

But in the cities, in Frankfurt or Paris, everything went far too quickly and was over before it had begun. Baudelaire’s “fleeting beauty… whom I might have loved” was his poetic take on the one-person model. But even then it was too quick, she had disappeared around the corner before he reached the end of the poem, leaving only the sense of possibility and the verse lodged in my memory.

Of course, it is also possible to take a pragmatic approach to the one-person model: no-one is forcing us to stand there as if struck by lightning, in the middle of the crossroads, to let fate run us over. We can/may/should grasp the opportunity, or at least look the person in the eye and ask them “is it you or not?” The right one would understand immediately, the wrong one would at best give an embarrassed or irritated smirk. So what? If you don’t ask, you don’t get. But, as I have found again and again, who really has the courage to be so forward at such a vital moment? And then to face the predictable disappointment, the realisation that yet again they were not “the one”, but just Mr or Ms Bloggs, no different from all the other millions walking around, all those other lost halves.

Sometimes, seeing the laughably low success rate of dating sites which purport to serve the one-person model, I ask myself why the dear Lord or whoever else may be responsible for our happiness can’t set up some sort of search service for love? I mean the sort of missing‑person databases that are used after major wars. The Red Cross uses them to reunite missing children with their parents, often quite successfully. Why shouldn’t such a fundamental existential service also be available for lovers? Plato wouldn’t have had anything against it. “Who has lost this person? Me, unique and meant just for you. Where are you? Please make yourself known if our paths cross on the underground or in the supermarket. A quick flash of the matching signal light will do.” The adverts in the huge central love computer would go something like that, with a few biometric details, saliva and scent samples, family tree and salary details. But the most important thing would of course be the personal bar code, the secret number for happiness, for example 0ll1lllll11lllllll0ll. That bar code would contain all the necessary information, absolutely everything. Who I am and why and for whom. The huge computer would then split all the data up into small pieces and vaporise it in its innards until it drew the right person for me: 1ll0lllll00lllllll1ll, for example. I could imagine that. Mr and Ms “Right” would be called immediately and introduced to each other by the happiness police. “Happiness is achievable,” would be the advertising slogan. “Congratulations, you are the missing half, let happiness in! Resistance is futile.”

But then, would I even recognise happiness if it appeared in front of me with no warning? Have I, in fact, already come face to face with it? Not the euphoria of hours spent alone – no, that is not what I mean. There must surely be something else, something – how should I explain it – more real, more major, more central, or rather: something that goes beyond the limits, something that is more surprising and above all larger than solitude. Not the happiness of whirling through an empty flat at midnight accompanied by a soundtrack of African drumming, a pulsing and pounding bass and vibrating violins – spinning from rug to rug, leaping through doorways and up steps, pausing in front of darkened windows to study my moving body. When the whole wild tumult of the music, its majesty and misery came together to create a kind of storm inside of me, yes, that felt a bit like happiness. It was the small, quiet and sad sense of triumph that I was still alive, moving, vital, free and beautiful – and the wonder of knowing it. A feeling that might have been soft and childlike, perhaps evocative of old-fashioned words like “humility” or “grace”, if there hadn’t also been all that wildness, which was stronger, louder and more obvious. This midnight happiness, this form of self-actualisation, this soaring, swirling, circling metamorphosis, this kind of happiness I knew well. But how should, how could, happiness with another, with one single chosen person, begin?

Perhaps it would be like that time in Frankfurt. Not at the airport, but at the train station, platform 6. This time we had arranged to meet. It was a sultry evening, there was a sense of something in the air – something indefinable, intangible. I had been worried that you wouldn’t come. I stood at the end of the platform, a plastic bag in each hand, provisions for the whole weekend. We didn’t intend to leave the hotel room. That’s what we had agreed. I had travelled from the south-west and you from the north-east of Germany. Frankfurt, with its dense mesh of criss-crossing routes, was the obvious place to meet. There, in that huge transport interchange, paths really do cross – without the help of a central computer or matching signals. Where, if not in Frankfurt, could a meeting between two not-quite strangers take place?

Your train was half-an-hour late, so there was no chance that I would miss you. I put the bags down on an empty bench and stood next to it, waiting. Your train pulled in and the doors opened, people spilling out onto the platform. You were not among the first off. I continued to wait, for maybe only two more minutes, and then I spotted you through the crowd. Tall and dark, with your quick, stiff, impatient movements which even then, right at the start, confused me and threw me off guard. I forgot the bags and went a few steps towards you. And then you were in front of me with a laugh, a shake of your head, a quick – almost peremptory – peck on the lips. Then you took my hand – that is, your right hand took my left – and gently turned me so that I was walking in your direction. And from that point on everything happened in a kind of sleep-walking haze. You were the one and only, I knew it immediately, the one I had always longed for. And yet I myself had split in two, one half walking hand in hand with you and the other standing watching and somehow knowing everything already. Accompanying everything that we did from that point on – crossing the too-broad streets, talking and walking in the rain, looking for somewhere to buy champagne, for a taxi, for our hotel – was an inner astonishment, a sense of wonder, a smug feeling of disbelief that made every one of your gestures seem to be in slow motion and left me hanging on your every word as if it were your last, or first, or indeed only utterance…

If you had stayed with me after that weekend, the many-people model would not have stood a chance.

The many-people model is more complicated than the one-person model – more complicated and perhaps also more chaotic and more primitive. Instead of a central computer, it is based around the idea of animism. In monotheistic religions, people believe in a big universal plan, while in polytheism all the spirits are equal. And so all those missed chances are up there in heaven, stored there or just temporarily parked. In the waiting room of happiness (what a good title that would be for a ballad or a romantic novel), they all hang around together – all those people who pass through our lives, the man from Frankfurt airport, the guy from the Piazza in Florence (or was it Turin?), the fleeting beauty from the old Paris backstreets, they are all there – wandering about restlessly from door to door. More and more of them all the time – hey people, stop pushing, there’s room for everyone up here! Even you!

Like hopeless shadows they cling sullenly to the walls, grumbling about the bad food and generally making each other’s lives miserable. Just yesterday the man from the escalator got into an argument with the Piazza guy again. It was, as usual, about which of the two of them was most likely to be the real one. Escalator man was convinced that he would only have had to hold out his hand and I would have stopped, while Piazza guy insisted that his voice had left the more lasting impression. I have given up getting involved in trying to settle such shadow fights – they would both be so shocked to find out how interchangeable they are, how meaningless, mere placeholders, boarders in the paradise of nowhere.

Because there is you, and you are with me, here and now. Of course, you sometimes feel the need to stretch your legs, breathe some fresh air, wander around and act as if “we” didn’t exist, as if I had missed you or only made you up. Poppycock and balderdash! I knew weeks ago that it must be you, I had proof. We were walking along the shore together – not the gulf of Guayaquil or Acapulco, but the banks of the Seine (or was it the Rhine or the Main?). It was damp underfoot as we walked and our feet pressed into the soft ground. You were holding my hand and it felt good being with you. I glanced behind me and there I saw, quite clearly before a wave washed them away, our footprints in the sand: 0ll1lllll11lllllll0ll and 1ll0lllll00lllllll1ll. And I knew that somewhere up there, somehow, whether among the shadow people or in the central computer, it had all been worked out.

Story from the collection Blaue Stunden by Sabine Haupt

Translated from the German by Caitlin Stephens

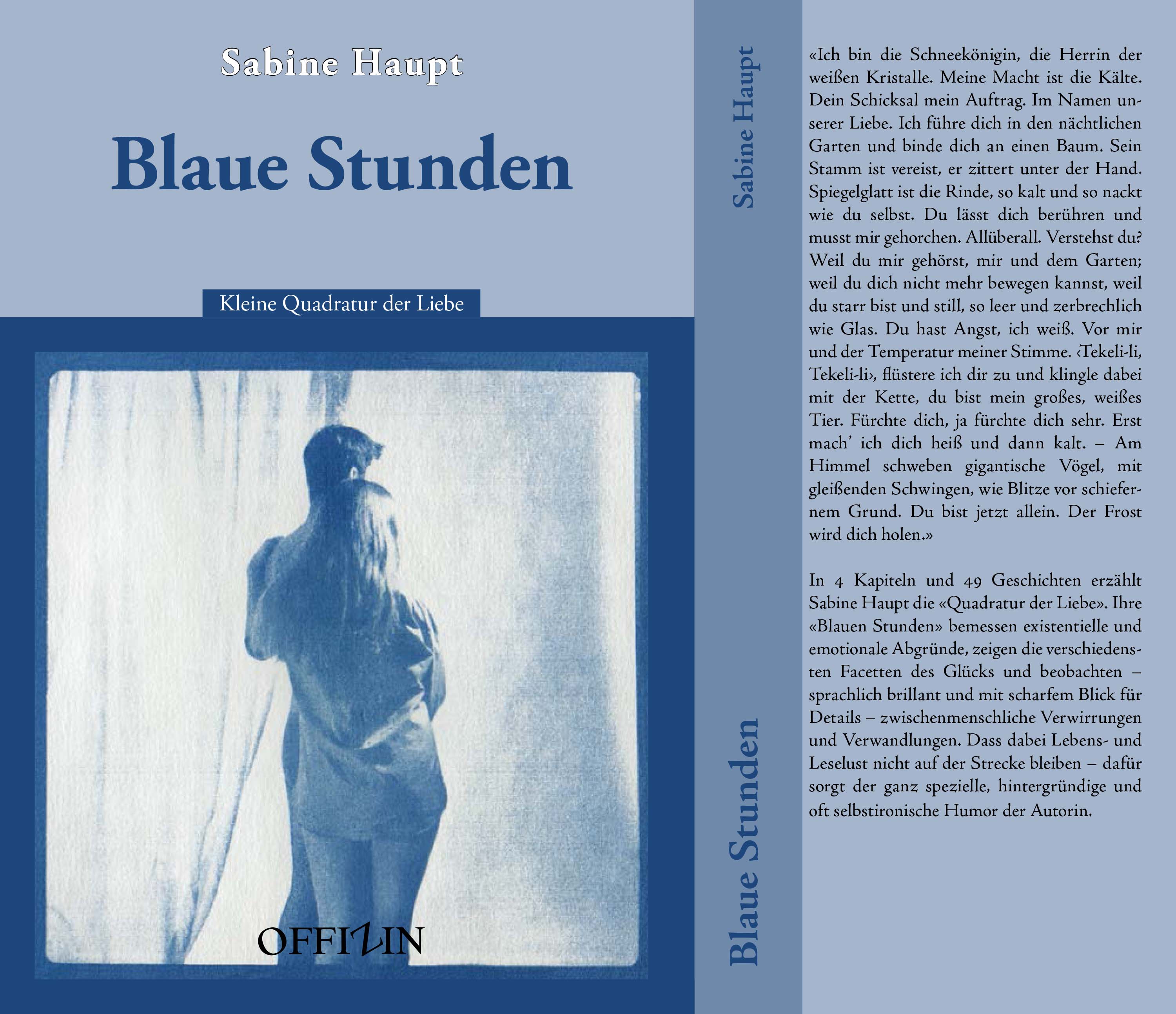

Original-Cyanotypie von David Gagnebin-de Bons (Lausanne):

© David Gagnebin-de Bons 2015  Titelcover "Blaue Stunden"

Titelcover "Blaue Stunden"